The history of the Abbey

Classified as a National Heritage Site (« Monument Historique » since 1947), the Abbey of Saint-André and its gardens have ties to many historical periods. From its beginnings as a modest hermitage in the 6th century, it grew to play a role in international history with its most glorious periods in the 13th and 14th centuries.

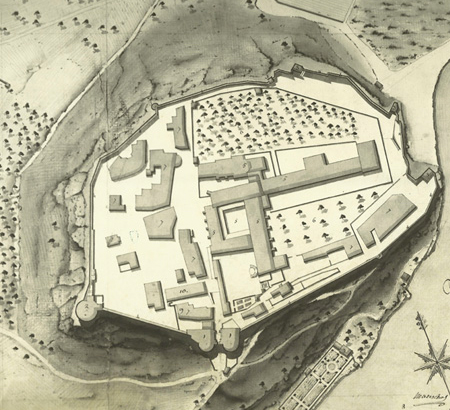

Mount Andaon’s elevation of 68 meters (223 feet) and its location on the right bank of the Rhone River give the site a strategic geographical position probably envied since Gallo-Roman times.

In the second half of the 6th century, Casarie, like many other hermits of her time, retreated into a cave to pray and meditate. Her hermitage was on Mount Andaon, where she died in 586. The veneration that surrounded her tomb led to the creation of an important cemetery on the hill and of a religious settlement on the site, although its situation remained precarious for many years. By the 10th century, the community was following the rule of St. Benedict, and it appears to have been formally constituted, approved in 982 by Garnier, Bishop of Avignon, and in 999 by Pope Gregory Vth.

The power of the monastery increased rapidly. While a chapel now stands on top of the holy cave, churches were erected on both sides of the former cemetery: St-Martin in 1024 and St-André consecrated in 1118 in the presence of Pope Gelasius II. At that time, Pope Gelasius’ bull enumerated the 80 priories on the two banks of the Rhône that already depended on the Abbey. In the 13th century, after the siege of Avignon by King Louis VIII of France and its eventual capitulation, a new chapter opened in the history of the Abbey with the act of union in 1226 between Abbot Bertrand de Clausonne and King Louis VIII, confirmed by Philippe Le Bel in 1292. The act of union recognized the seigneurial rights (rights to rule) of the abbots of Saint-André, and liberated them from the control of Avignon. The agreement allowed the construction of Fort St-André, which was an important outpost for the Kingdom of France and the Capetian dynasty, since the fort faced Avignon where the papacy was established in 1309. The fort was completed around 1372 and remains among the most remarkable 14th century fortifications in France.

The 13th and 14th centuries were the peak of prosperity for the royal Abbey. The number of monks rose to more than 90, and an inventory done in 1307 reveals the magnitude of its treasures and its vast library. The Abbey held a vast domain to which were added the revenues of 211 priories in the Languedoc region and Provence. The dark years of the 15th and particularly the 16th century marked a period of decadence and decline.

In 1637, with the installation of the Congregation of St. Maur and a resulting spiritual revival, an ambitious program of reconstruction of the monastery began with designs and oversight by Pierre Mignard, King Louis XIV’s architect. The Church of St-Martin, whose vault had collapsed in 1603, was rebuilt and redecorated with red marble columns and a monumental altarpiece, and the chapel of the Virgin was added between the two churches. High walls surrounded the domain, which was dominated by the chapel of St. Casarie atop Mount Andaon.

The Abbatial Palace was of typical classical design with a large two-story building standing on a terrace supported by powerful Piranesi-style vaulted arches, the ensemble completed on each side by matching three-story pavilions with pediments. In the 18th century, the architect Jean-Ange Brun redesigned and rebuilt the entry courtyard and added beautifully vaulted rooms to its pavilion. These additions and improvements vividly affirmed the power of the Church, a sharp contrast with the reality that only 11 monks were living there in 1790.

On September 3, 1792, the French Revolution drove the last of the monks from the Abbey. At first converted into a military hospital, the Abbey was sold to an estate agent who decided to demolish it and sell the materials. The only building spared was the beautiful entrance pavilion, which served as housing, and the large terrace supported by its magnificent vaulted arches survived also, witness to one of the most important monasteries of southern France.

In 1868, the congregation of the Sister Victims of the Heart of Jesus settled at the Abbey. It was bought ín 1913 by the painter Louis Yperman, known for his restorations of the frescoes of the Popes’ Palace in Avignon, and he established an orphanage at the Abbey. It was during this period that his friend Emile Bernard executed the cycle of three murals on the ceiling of one of the vaulted rooms.

It was in late 1915, during her stay in Villeneuve, that Elsa Koeberlé discovered the Abbey Saint-André, which became the center of her existence until her death in 1950. Daughter of Dr. Koeberlé, art collector and friend of artists such as Antoine Bourdelle, she published her first book of poems at the age of 21. Having escaped Alsace in 1914 just before the German occupation, Elsa Koeberlé met Gustave Fayet in 1916. He bought the Abbey Saint-André for her in August of that year, confident that he would be repaid when the German occupation that froze her assets ended.

Born in Béziers, Languedoc, in 1865, Gustave Fayet was a painter, ceramist, and famous collector of the works of Van Gogh, Gauguin and Redon. He had just recently purchased, in 1908, the Cistercian Abbey of Fontfroide, near Narbonne. After the war ended and she regained access to her funds, Elsa Koeberlé repaid Fayet and devoted her entire fortune to the restoration of the Abbey, without ever wanting to change, out of gratitude for his support, her status as “tenant for life” of Gustave Fayet.

Elsa Koeberlé’s friend Génia Lioubow, writer and painter, lived with her at the Abbey, and the two women shared the work of restoring and improving it until Génia Lioubow’s death in 1944. She left behind a substantial portfolio of paintings and drawings.

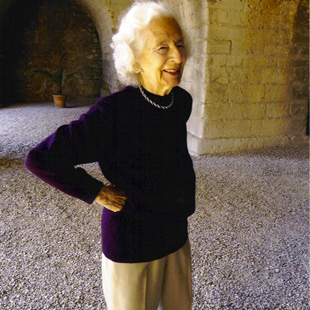

In 1950, the Abbey passed from Elsa Koeberlé to Roseline Bacou, a granddaughter of Gustave Fayet. Head curator of the Graphic Art Department of the Louvre Museum in Paris, Roseline Bacou continued major restorations at the Abbey with the help of the Center for National Monuments, which supports National Heritage Sites (« Monuments Historiques ») in France. Passionately devoted to the development of the Abbey of Saint-André and its gardens, Roseline Bacou opened them to visitors for the first time in 1990. Since her death in February 2013, her family continues the task of restoring and improving the Abbey with equal energy and commitment.